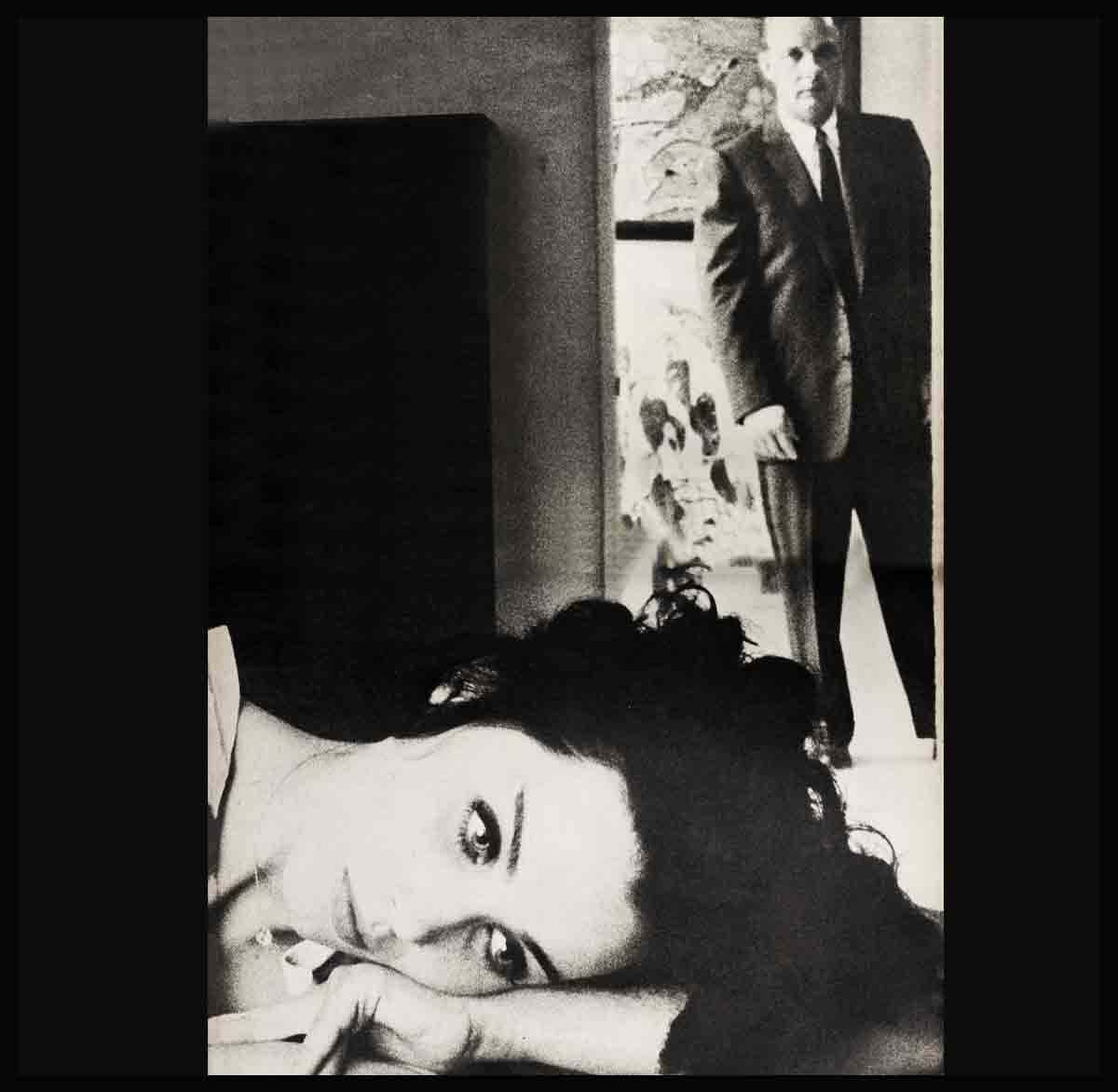

The Man Who Runs Up Hills—Robert Horton

Once there was a fellow named Meade Howard Horton, Jr. At 17, he weighed a fat, embarrassing 205 pounds; he’d had a serious kidney ailment since he was ten, and one day, when he was trying out for football, he had to leave the scrimmage because the pain was so unbearable. His coach stared scornfully, then turned to one of the other players. “Horton would like to play,” he sneered, “but he says he has kidney trouble. I think he’s just yellow.”

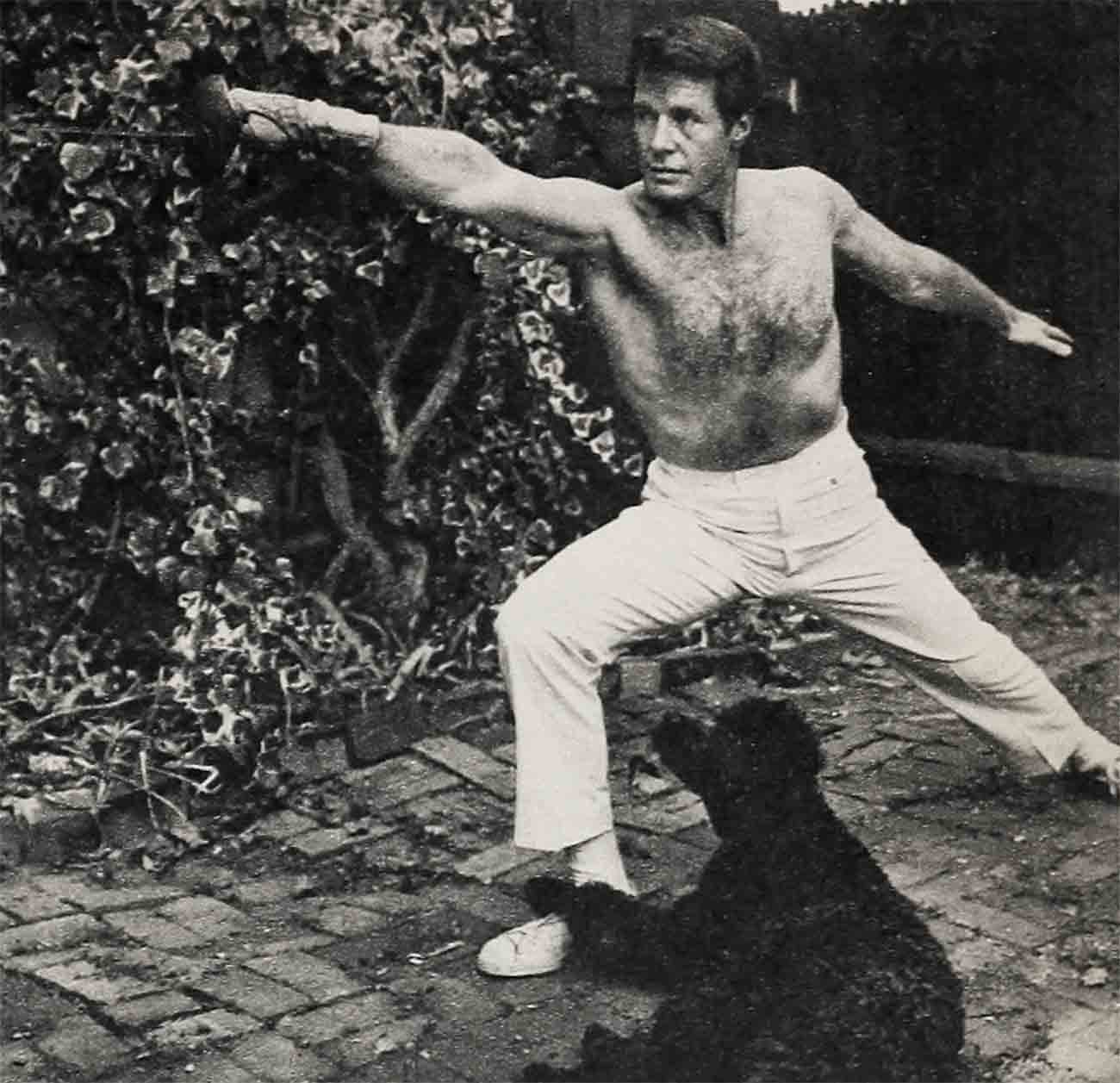

Just the same, there came a day when Meade Howard Horton, Jr., slimmed to a sinewy 175 pounds, stepped forward as a high school senior and accepted a small gold football as the running guard on Harvard Military Academy’s championship football team. It was one of the memorable days of his young life.

Meade Horton, Jr., isn’t around any more—he’s Robert Horton now—but, at 34. he’s still a stubborn, rust-haired man who remembers something his father told him and has been building his life by that philosophy ever since.

It moved him out of the ranks of nobodies in second-rate movies and lifted him to stardom in TV as Flint McCullough of the popular NBC series, “Wagon Train.” But more than this, it has helped make Bob much of the man he is—a dominant, mature person who generally knows what he wants when he wants it, and then goes out and gets it.

The advice? “It was really simple,” says Bob. “For years I didn’t understand it—or didn’t want to—but when I did, it virtually changed my life. ‘Look, boy,’ my father said, ‘you don’t get any stronger walking downhill. It’s the uphill walking that gives you muscles.’

“That, and what TV producer Joan Harrison once told me—‘to be politely stubborn’—have had a big impact on my actions. I think I was chosen for ‘Wagon Train,’ after nearly 30 other candidates had tested in a tense scene against Ward Bond, because I stood up to him in that scene and wasn’t dominated. I knew I had to run uphill.”

This faith in his beliefs has Bob playing Flint McCullough as though he had invented the lean-muscled trail scout. The way Horton sees him, McCullough is a refined, well-educated man who refuses to behave as a celluloid cowman is supposed to behave. “Why should I act like a movie cowboy?” asks Bob, quite logically. “I’m not a movie cowboy, and most of the real cowboys of the 1870’s weren’t, either. They were from the East, some from England and Ireland, and a lot of them were well-educated.”

In the bright, sometimes fragrant lexicons of Westerns, there are certain time-honored cliches which only the most daring would defy. First, there are the “white hats and the black hats”—the good guys and the bad. There is the historic “Trampas Walk,” that scene where Gary Cooper or Burt Lancaster walks defiantly up the middle of the main street, arms bent slightly, the palms of his honest hands curled near the butts of his six-guns, while his enemies, all ten of them, wait in the sinister shadows of the Red Dog Saloon. There is, most of all, the movie cowboy who wouldn’t be caught dead unless he can squat down on his hunkers, pick up a stick and draw a picture in the dirt, saying, “Wa’al, now, there’s how fur it is to the rustlers’ ray-veen.”

And then, of course, there’s Bob Horton, a frontiersman with manners and a style—the last man you’d expect to find among the buffalo trails and the sagebrush.

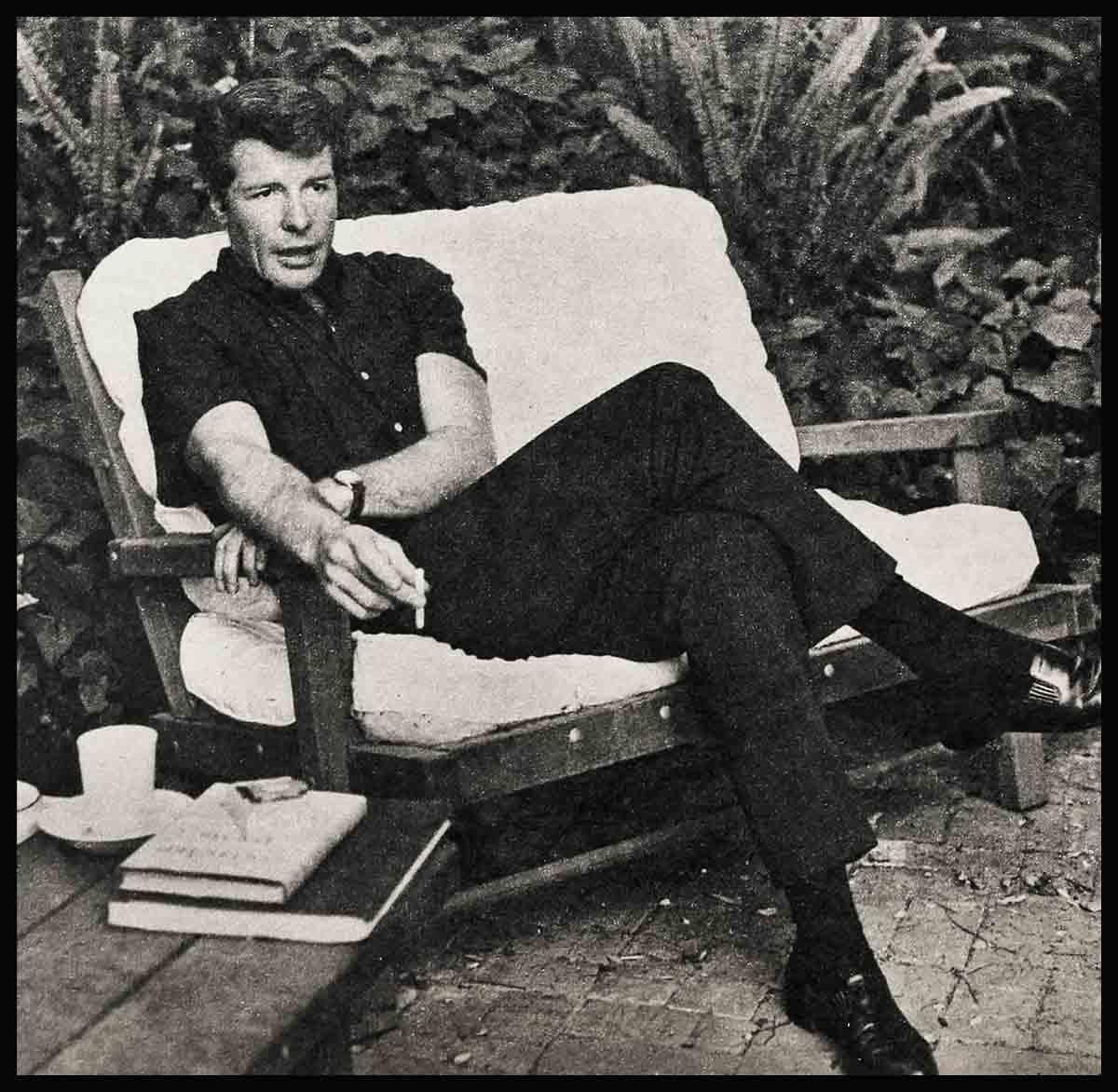

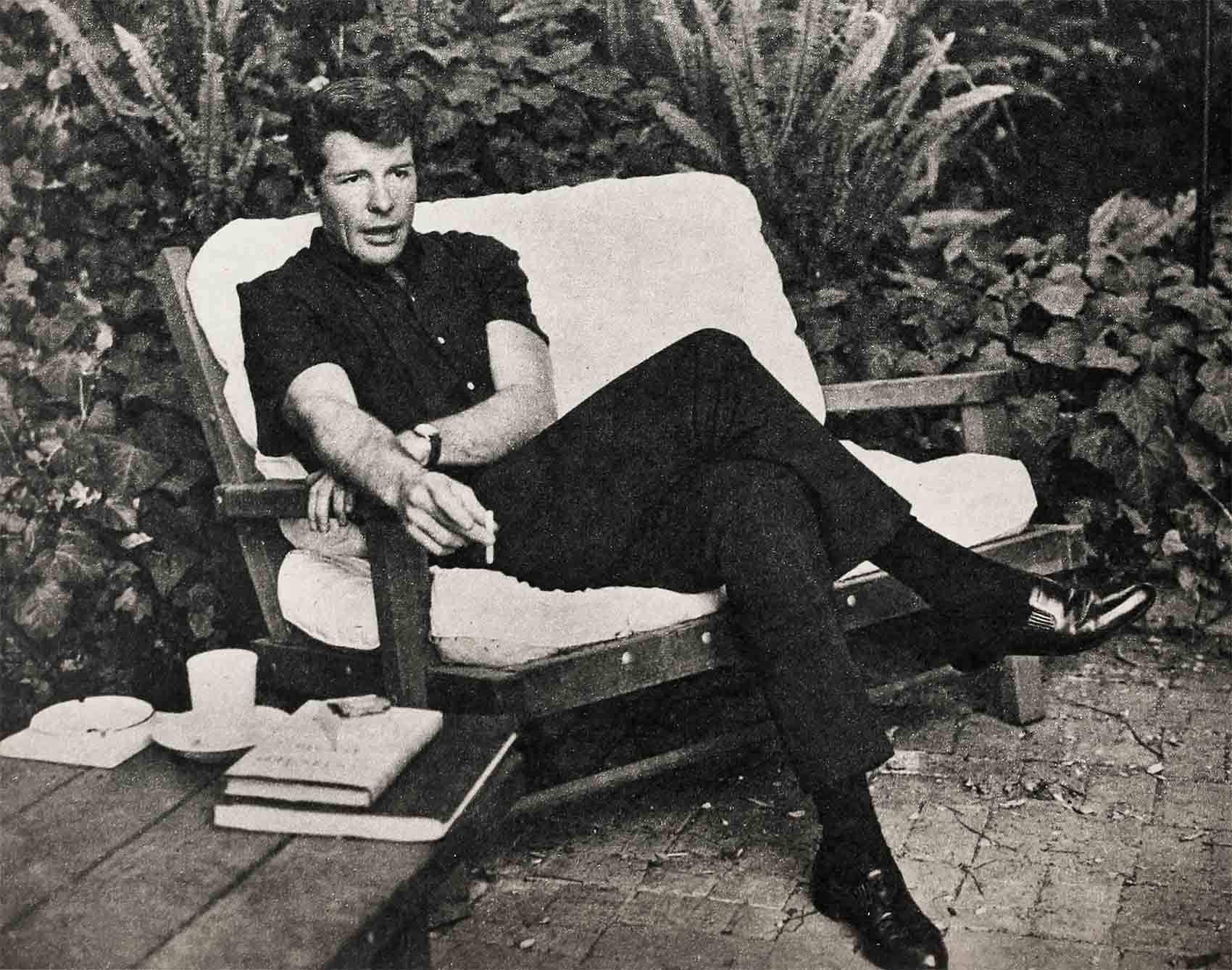

In a sense there are two Bob Hortons: one who rides the plains each Wednesday night for “Wagon Train,” and another who rides his white Thunderbird the balance of the week. If this Horton has a pair of leather chaps or a set of silver spurs or even a dress-up Stetson around his house, he keeps them well-hidden. The only “deadly” weapon Bob has is a coffee table made out of an ancient smithy’s bellows of heroic proportions. It ends in a pointed black steel spout which few people can see against the brown and black Navajo rugs on the floor. Unwary guests almost always bark their shins-and let out a painful “Ouch!” when they first encounter Flint McCullough’s favorite coffee table—and that is all the lethal armament you’ll find at Mr. Horton’s.

But the man who lives in a tiny house like something out of Sherwood Forest is a strong and obstinate fellow; don’t think he isn’t. “I’ve had the same house now for four years,” Bob says. “and there’s no reason why I should move. I even have the same telephone number. I can afford to buy an extra suit or so, now, and take a friend out to a really good restaurant, without worrying about the cost. But beyond that there have been few changes since I got on ‘Wagon Train,’ and I don’t plan on any big ones, either.”

Some of Bob’s critics have said, “Horton never did amount to much on Hollywood’s picture sets, but as trail scout for ‘Wagon Train,’ he’s in his element at last.” This doesn’t upset Bob at all. “I can’t resent my failure in pictures,” he remarked, tranquilly. “I don’t see it as my fault; it might have been just the stories or the times.”

Still, just getting the role of Flint McCullough; after all those dreary movies, was not unalloyed happiness for Horton, either. It was merely a beginning, not the end. Once again he had to prove his stubbornness—his belief in what he felt was right. Though Bob feels he has won his spurs as Flint McCullough, it has been far from easy. Rightly or wrongly, he felt he was being pushed around—and Bob has always resented being pushed around.

When he was first chosen for the series, it was understood that he would be co-starred with old-timer Ward Bond, who plays the Wagon-master. “Before the show was a month old,” Bob laughed ruefully, “I began to feel like a hired hand who has been voted out of the bunkhouse because he snores. It was tough sharing something with a guy like Bond, who has been around for 30 years. I never seemed to get any closeups, and the viewers sitting at home didn’t know who I was, even in the minor action.

“Not that there was a feud between Bond and me. He’s fine to work with. Ward’s been in the business a long time and he’s worked with many of the crew and most of our guest stars before. But doing a Western was exactly Ward’s element. I had to find mine.”

Bob had already done one thing few other actors would even dream of. “I was vacationing in Cuba,” he recalls, “when I got word that I had the part in ‘Wagon Train.’ I drove back to Hollywood along the same route the old pioneer wagon trains used to take—Dodge City, Denver, Salt Lake, Reno, through the famous Donner Pass and on to San Francisco. I guess I’m a man endowed with a big lump of curiosity. I poked around looking at plaques and cemetery inscriptions, getting a good, solid feel for the terrain our ‘Wagon Train’ was to follow.”

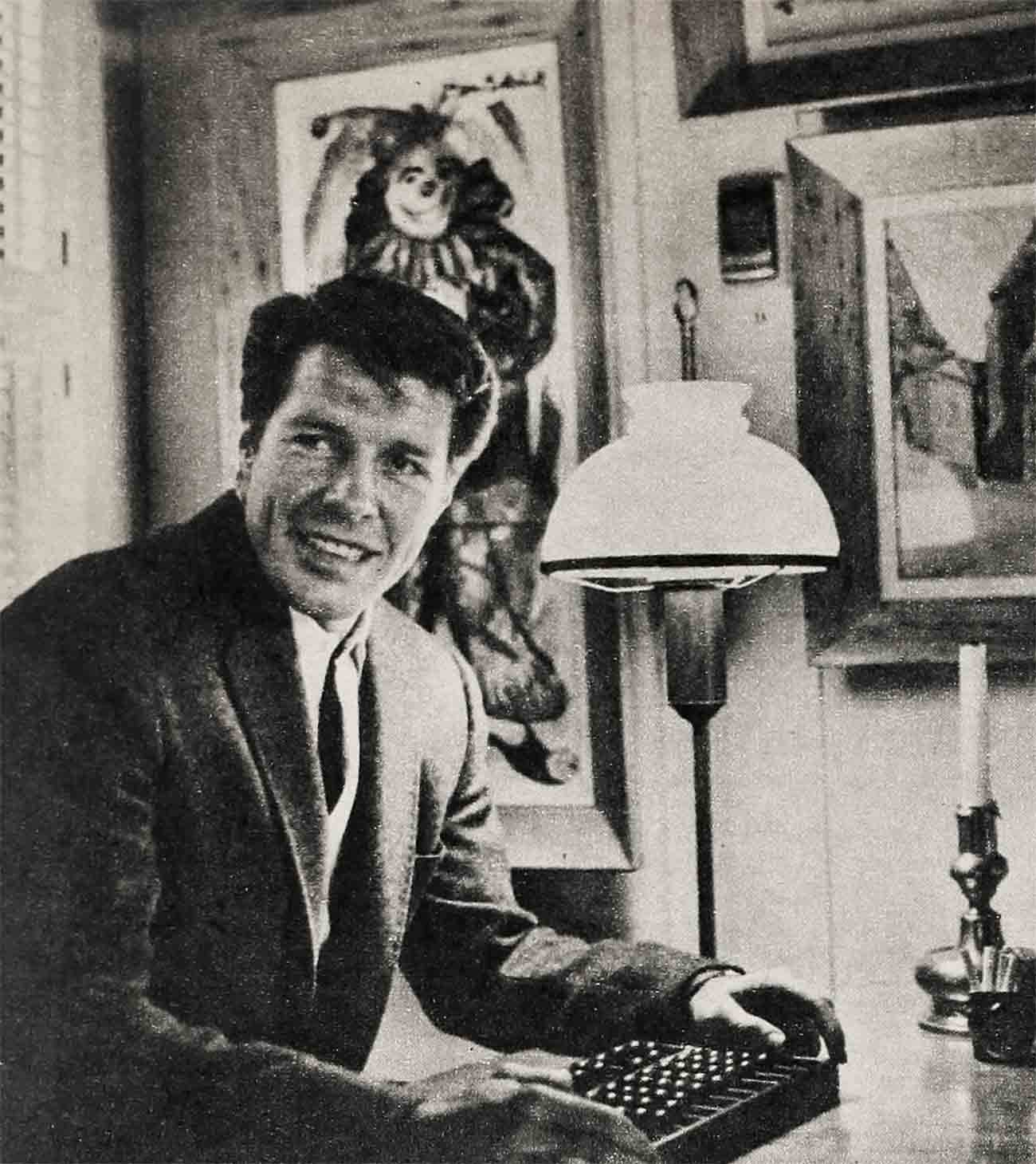

But when Bob began to feel like “the hired hand who had been voted out of the bunkhouse,” he knew that once more he’d have to start walking uphill. Or even running. He preferred to believe that what seemed like pushing. around was not intentional on any one’s part. “So I sat down,” said Horton, “and wrote a detailed sketch of Flint McCullough and gave copies to everyone connected with the production of the show. I remembered that in one story with Shelley Winters, nothing was said in the entire script that shed any light at all on McCullough’s character. I felt that biography I had written would eliminate my being dropped into a story without any explanation of who I was.”

If that was being a ham, Bob let the carpers make the most of it. The truth is. Bob’s sketch of the imaginary McCullough reads as though he had known the trail scout personally. “It’s so good.” said one associate. “that the producers of the show have had it mimeographed and sent around to all the writers. In fact, it’s much more complete and colorful than the biography NBC has put out on Horton himself.”

Bob had cleverly made Flint his baby, so his next step was to hire his own press agent. “No, my head size didn’t suddenly expand,” Bob laughed. “But it was only natural that most of the news sent out on ‘Wagon Train’ would be about Bond. He was known and I wasn’t. My film and TV roles since 1951 haven’t been the kind that turns one into a star.”

As for the forthright, outspoken Ward Bond, he was unperturbed. “There’s no feud between Bob and me,” he said. “I’ve got a lot of respect for this boy as an actor. In fact, I’m the guy who picked him for the part in the first place.”

And since Bob was to be co-starred, he wisely saw to it that he got some of the sweets of stardom. He asked that his name be put on a chair for him on the sound stage where the show is filmed. He also requested—and got—a special parking space reserved for him on the studio lot. “These things may seem silly any place else,” Bob said, “but I’ve discovered they’re important in Hollywood.”

For that matter, the stubborn Mr. Horton has always fought—or tried to fight—for his rights, even if it. meant being tagged a maverick. If confidence was needed, he had it, or he put up a confident front. Not long ago, columnist Hedda Hopper remarked, “When I met Bob Horton at a Gary Cooper party some years ago, he was a pretty confident young man. ‘Keep your eyes on me, Hopper,’ he said. ‘I’m going to be a big star.’ And by golly, he’s made good. He’s the life and soul of ‘Wagon Train.’ ”

But most of all he’s been a rebel—at times, an obstinate, hot-headed one—since childhood. He’s a native Californian, born in Los Angeles, July 29, 1924; but between the ages of ten and 14, young Meade Howard Horton’s life was a nightmare of pain, operations, physical breakdowns and emotional disturbances so lacerating that it was only a few years ago he became free of them. That was when an analyst to whom he had been going for almost four years, shook his hand, smiled and said, “Bob, I’m happy to tell you that you don’t need me any longer.”

The kidney ailment, which first laid him low at ten, required two years of weekly trips to a doctor’s office. It also brought the youngster the loss of physical strength and memories of pain he still shudders to recall. Finally there was an operation. The operation was successful, but within a few months he was again forced to the hospital with an emergency appendectomy. “Those were the years,” Bob remembers now, “when the family doctor or my parents were usually telling me, ‘You can go out and play now, an son, but take it easy.’ ”

This only added fuel to his rebel nature. “I thought, like most kids, that my parents didn’t understand me,” Bob said. “Everybody at home was picking on me.”

The Hortons were a family of’ doctors, lawyers and other professionals; they were also Mormons and held devoutly to their religion. Bob’s older brother Creighton was thrown up to him as a model of decorum; and it infuriated the younger boy when some member of his staid and prosaic family said, “For goodness’ sake, Meade, why must you become an actor?”

“But I didn’t want to be trained for a ‘sober, staid’ profession,” says Horton. “I wanted something else. Out of sheer frustration I ate so much I ballooned out to over 200 pounds. I guess my family’s lack of encouragement really hurt me. So I sloughed off school, did a lot of crazy things. I’m not proud of the antics I pulled as a youngster, but something inside of me forced me into mischief. I even ran away from home at 16, but I didn’t get far. Used up all my money.”

He was still a teenager when the War came; he enlisted in the Coast Guard and served for several years. For two years after his discharge he worked as a cook, dishwasher, restaurant cashier and in other menial jobs to “find himself.” At 22, he was old enough to know better, but he was still getting into mischief. Then he jumped into a hasty marriage. The girl was a non-professional, a quiet miss named Mary Katherine Job. Horton was just too hot for anyone to handle; his fiery temper turned minor irritations into major explosions. The marriage didn’t have a chance. Today Bob still speaks of Mary with affection. “Mary and I see each other now and then,” he says. “About 85 percent of the breakup was my fault. I was too immature to know what I was doing.”

Yet, somehow, Bob managed to get a little sense into his head. He made up his mind to study dramatics, entered the | University of Miami, then transferred to UCLA, where he completed the four-year course in two years and nine months. He also graduated with honors. By this time he had adopted the simpler “Robert Horton,” (probably still in rebellion against his family), then managed to snare a minor acting role in a comedy called “I Give You My Husband,” at the Jewel Box Theatre.

“It paid me exactly nothing,” Bob revealed. “They gave me the part because it called for red hair. Still, I enjoyed that role just as much as if I were doing it perfectly, which I wasn’t. I was searching, throwing my weight around, trying to find myself in it.”

Even so, there was still no rousing demand for Robert Horton, with or without red hair. He knocked around for several years, getting a TV spot here and there. His prospects turned so bleak that he finally took a job as a greeter in an all-night restaurant, spending his days in search of TV jobs. Finally he landed a small part in “Suspense,” and then a couple of even bigger roles because he had impressed the director. He went from bit player to star in three weeks.

Now the film studios began bidding for Horton, though only a short time earlier, he couldn’t get inside a studio gate. He landed a Warner Bros. contract which lasted for one film, a Fox deal which ran for two, and finally was signed by MGM, where he did seven pictures in two years.

“I got real hot after my first couple of pictures,” Bob said. “Don’t ask me how you get hot, or why, but you know it immediately. People started clapping me on the back and calling me ‘Mr. Horton.’ All over the lot they were searching for a new Gable. Then, just as suddenly, I got cold. I was plain Bob Horton and was put into a production unit that made only one.good picture—and without me in it.”

By now he was ready, or thought he was, for another try at marriage—this time to Barbara Ruick, a young actress who had appeared in “Carousel.” The two eloped to Las Vegas for a Flamingo Chapel wedding in 1953, but again the combination was too explosive to last. Miss Ruick was seemingly not aware that another girl had once said of Bob, “I never know what to expect from him from one time to another. I doubt if any woman will. Bob fits no pattern. He seldom even looks the same twice. He is as inconsistent as the moon.”

The second Mrs. Horton testified in the divorce proceedings that her husband was “a completely self-centered person.” Barbara had filed suit twice in seven months, after various. reconciliations, and in court she said, “He wouldn’t come home when I expected him to. When I went with Bob to the opening of one of his plays, and later to a party to celebrate it, he gave all his time to other people. I was cast aside like a stranger.” The divorce was granted April 28, 1956, on the grounds of mental cruelty.

All Bob will say of his second marriage is, “Barbara and I should never have married. We were meant to be good friends—but never husband and wife.”

These days, his most frequent dates are with actress Nina Foch, who is the same age as Bob—34. They have much in common: a love of the theatre, a passion for dogs, a mutual distaste for senseless chit-chat. They get along well together, and both know what it is to

have been divorced. But Bob denies that theirs is a serious romance. “I’ve gone out with Nina quite a lot and like her very much,” he says, “but the report that we are getting married is far from true.”

Not that “Wagon Train’s” romantic trail scout is opposed to marriage. One of his closest friends remarked, “Bob doesn’t mind his bachelor life, but he really misses not being married and not having children. He feels depressed when he sees his brother Creighton, who’s a doctor, and his family. ‘I’d like to have what Creighton has,’ Bob has often said. But he’s been badly hurt several times, and he doesn’t care too much for Hollywood girls. They’re anxious to go out with Bob Horton, the actor, not Bob Horton, the man. That’s why I think the woman he marries will be someone not in the picture business.”

If it were up to the ladies who keep his phone ringing, Bob would probably be married tomorrow. Since his success with “Wagon Train,” there’s hardly a moment when his phone doesn’t ring, or his mail box isn’t stuffed with perfumed love letters. Teenagers phone, pretend they want a “Dexter” or a “Jimmy,” and breathe heavily when they hear Bob’s voice. Their little subterfuges amuse Horton, but he’s not above suggesting in a kind way that they cut it out. The fan mail is another problem—at least in one way—and Bob has had to admonish some of the more aggressive correspondents who suggest dates that he doesn’t go out with people he hasn’t met.

“The most astonishing note,” said Bob, grinning ruefully, “was one I got a few days ago. ‘Dear Mr. Horton,’ it began, ‘I would like to apply for the position of your housekeeper, dear!’ Now what do you do with a thing like that?”

“Indians and rustlers Bob can cope with,” a friend laughed, “but eager-beaver dames are a different story.”

Certainly, the way not to meet Bob Horton is to be aggressive and throw yourself at him. He does not like aggressive women riding herd on him. His philosophy is, “Don’t call me; I’ll call you.” What’s more, says Bob, “A man wants a woman around when he wants her around. If he finds out he wants her around all the time, he marries her—if she’s willing. But it’s the man who’s got to pop the question, not the woman.”

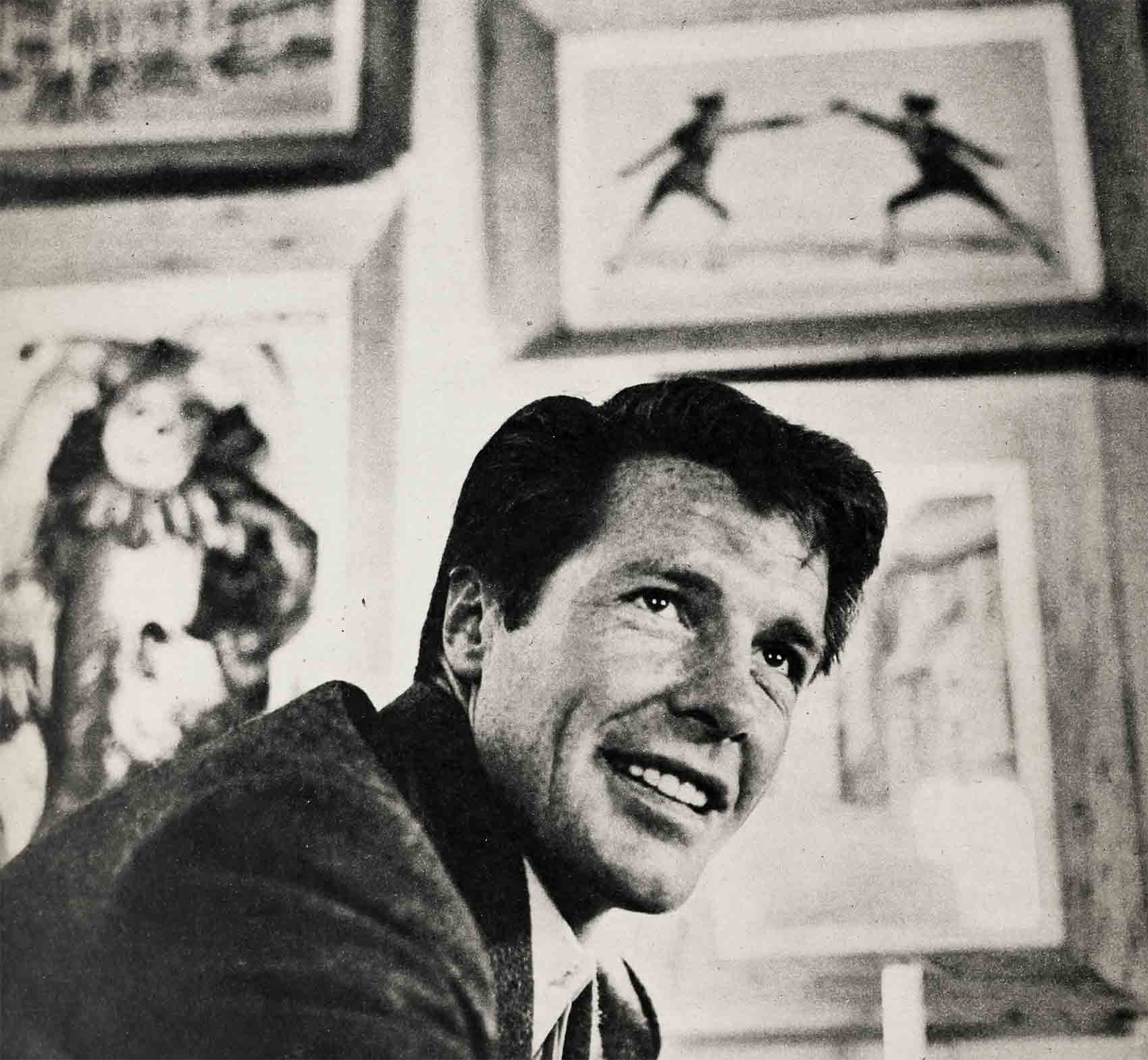

Yet with it all, Bob takes the huntresses and the avid letter writers with good humor. He is not flattered by his mere popularity as a top TV personality; he wants something more than that. Until he gets it, he’s comfortable and happy in his odd little house, just big enough for himself, his French poodle, and his collection of furniture that combines African, Asian and Mexican art into something that’s quite Early American. “If the guests turn out dull at parties,” Bob laughed, “everybody can talk about the odd furniture.”

When you go into his beamed living room, you have to squeeze between the arm of a modern love seat and the jib boom of a small ship model atop a pine chest. There’s one table fashioned from a century-old butcher’s chopping block, and a brick fireplace that holds a Franklin stove. There are ancient legal papers and handwritten contracts doubling as lamp shades. In Bob’s bedroom upstairs sits a king-size four-poster. with antique cobblers’ benches doing duty as night tables. But most of all, there is Bob’s famous coffee table, made of that bone-jarring ancient smithy’s bellows. He found it one day at a Santa Monica antique dealer’s back door, paid $50 for it, spent almost a week scraping, staining and waxing it—and today you couldn’t buy it from him for $500.

“I know my visitors are inclined to bark their shins against this monster,” Bob grins charmingly, “and some people have left here limping. But there’s been no serious damage to my table so far.”

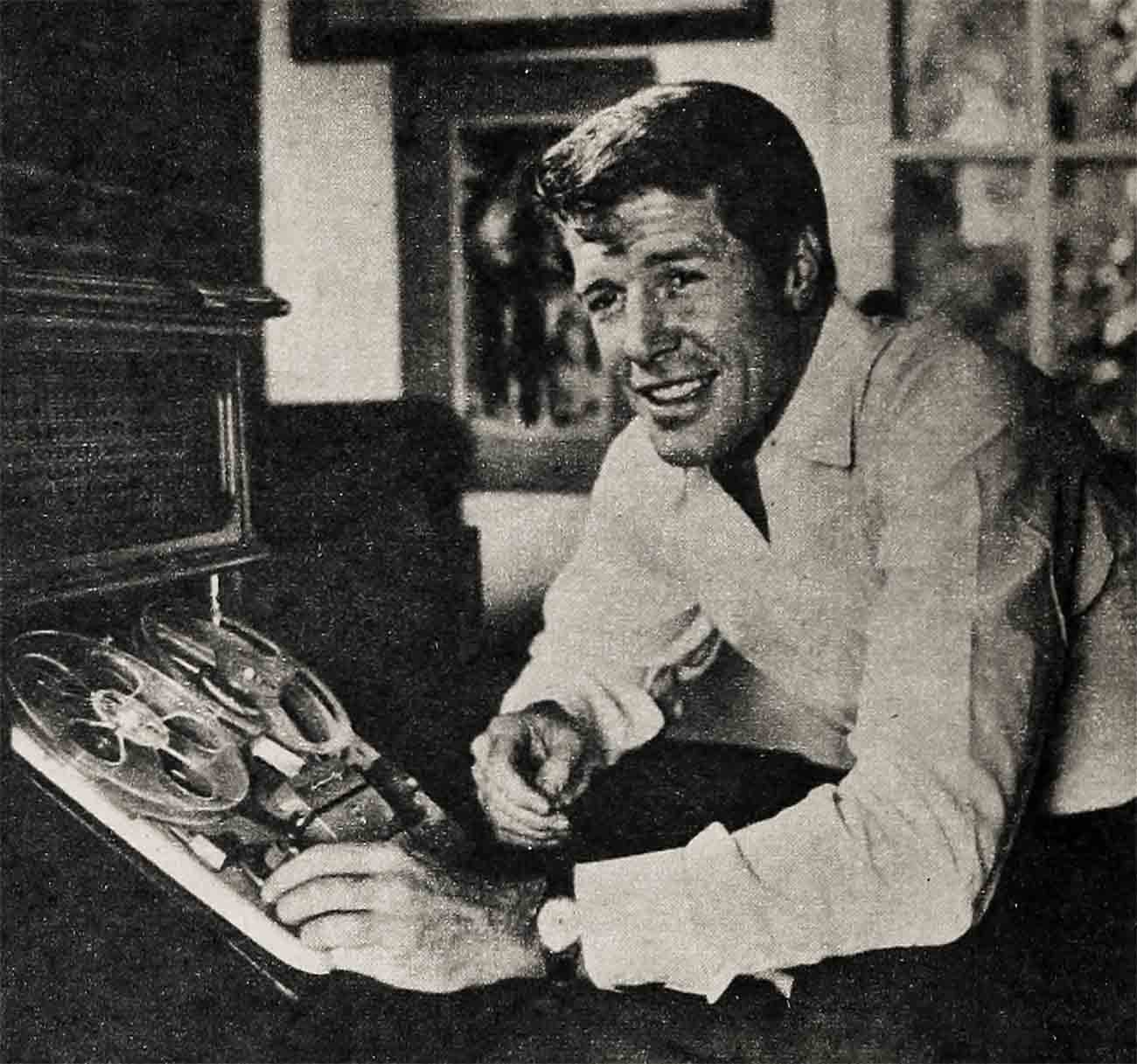

It’s all a joke, of course, because Bob is genuinely a gracious, friendly man, soft-spoken and courtly. Listening to his voice, you’re not surprised to discover that he’s also something of a singer, and wants to do a big musical. He is a lyric baritone; he has been studying zealously for years, and when he appears at a rodeo, he frequently sings before as many as 30,000 people.

“Nothing spectacular,” says Bob. “Things like ‘Don’t Fence Me In,’ ‘Spurs That Jingle, Jangle,’ or ‘Wagon Wheels.’ I usually pick up a guitar or drum accompaniment in the town. I can really sing when I work at it. But I’m going to have to quit smoking; it plays hob with my voice.”

If Bob is still stubborn at times, it’s because he knows that, for him, his stubbornness has been his salvation. He also believes he has the lines and the scars in his face to show that he has achieved a certain maturity. “This may sound cocky,” he said, “but I really believe I’m close to being a mature man. I have few close friends, but they are good ones. And I have a better understanding of myself now through understanding people. I’ve discovered that you just can’t run from trouble; you’ve got to face up to it and conquer it.”

His way has been good for him, that’s for sure. “Last year,” Bob chuckled, “I went to New Orleans and a few people stopped me and said, ‘Haven’t I seen you somewhere on TV?’ A couple of weeks ago I was there again, and they gave me the key to the city.”

THE END

—BY JIM COOPER

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1959

No Comments